As a math and political science student preparing to graduate from Whittier College in the '70s, Chester Fontenot Jr. told his professors that he wanted to bring America to its knees.

“I used to say when I was younger that I was going to start a revolution,” Fontenot, an English professor and director of Mercer’s Africana Studies program, said. “I had a burning desire to straighten out and to uncover and reveal the truth about people of African descent, there are so many misrepresentations."

His professors’ responses changed the trajectory of his life when they told him they admired his commitment, but that there were other ways to change the system. Despite his protests, they urged him to apply for graduate programs.

“They said, ‘You can be much more use to your people by working within the system and changing it that way,’” said Fontenot.

These are words Fontenot has lived by. After graduating, he went on to get a Ph.D. in Comparative Cultures from the University of California at Irvine and completed a postdoctoral study at Yale University. He is the author or editor of eight books and over 60 articles.

Despite his numerous publications, Fontenot said that the research project he is currently working on has quickly become the most important research of his life. The project aims to digitize the records of slave transactions in Middle Georgia and make them accessible to the public.

This research project began unexpectedly seven years ago when he was getting lunch with his friend Erica Woodford, the Bibb County Superior Court Clerk.

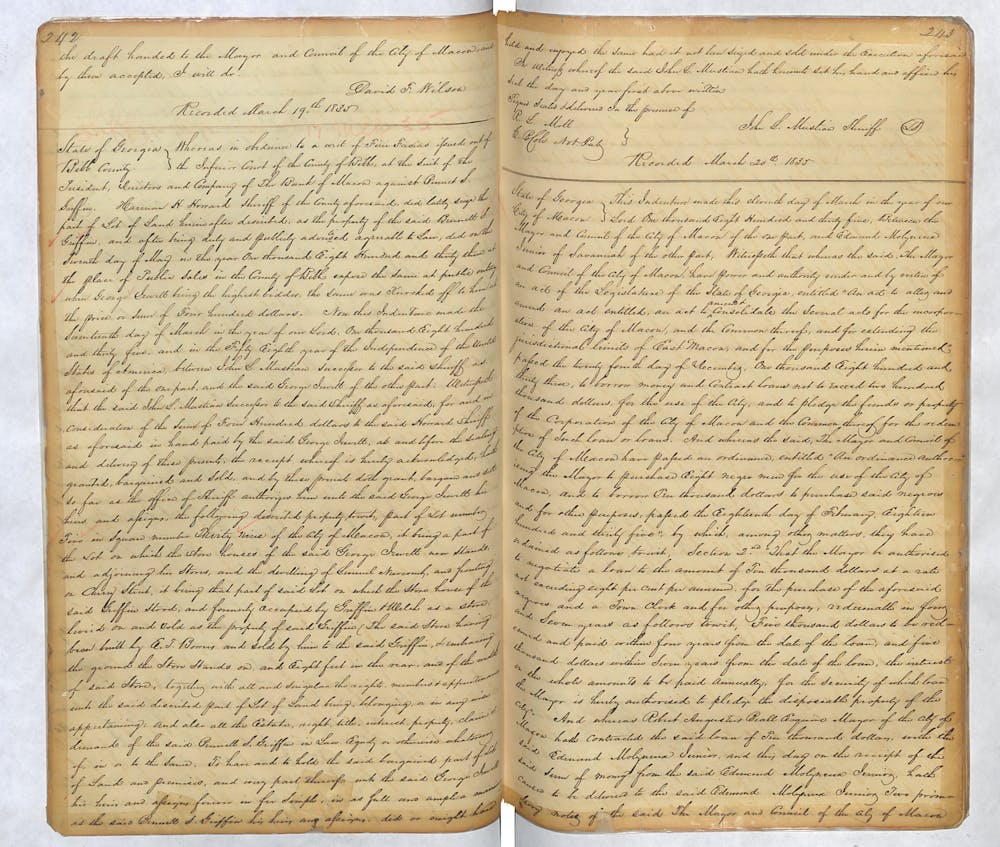

She told him she had been in the archives at the clerk’s office conducting inventory when she discovered records of slave transactions within deed books.

Fontenot immediately knew that the discovery was too significant to be left alone. This sparked the initial idea for what would become an ambitious research project, the digitization of over 6,000 pages of slave transaction records. The public will be able to access these records, which would be critical for researchers, genealogists and people trying to better understand what life was like for African-Americans in Middle Georgia in the 19th century.

Stephanie Miller (left), Brenda Williams (middle), Erica Woodford (right) and Chester Fontenot are the core of the research project "Digitizing Black Life and Culture in Middle Georgia." Photo provided by Chester Fontenot.

Mercer’s Department of Africana Studies, the Clerk's Office and Mercer University Libraries began working together in 2018 on the collaborative research project, which also involved various volunteers and a committed team of students. They focused on the years 1823 to 1865 when slavery was abolished.

The field of Africana studies differs from other academic fields because it requires the researcher to start from scratch — to first discover the data and then utilize it.

“My colleagues in English or history can go to archives and, you know, texts are there,” Fontenot said. “We have to go create, go find stuff. And then make it useful. And then we can do our research.”

The project entailed hours of meticulous reading through records in 18th-century calligraphic writing. Fontenot said this work was both physically and mentally demanding. Especially for Black researchers, the research took a significant emotional and spiritual toll on participants as the weight of history became all the more real. They were not just reading statistics in a book; they were reading about real people.

“After a while, you do this work and you can almost hear the cries of people being torn away from their loved ones on an auction block,” Fontenot said.

As the researchers gained a better sense of the data, Fontenot and his partners came to understand that Macon-Bibb used to be a major center for slave transactions in the Southeast. The documents could bring the stories of enslaved people to life and help the public acknowledge the scale of its impact.

“Slavery was not only legal. It was part of the fabric of life. It was part of the government where these deeds are in the courthouse,” Fontenot said.

The family names of wealthy slave owners found in the deed books are still prominent on streets and buildings in Macon today. While Macon has begun to acknowledge how slavery is a large part of its history, it still has a long way to go.

Especially now that the database has been made public, the research has gained attention from scholars and media outlets. Despite the attention, though, Fontenot feels as though people still fail to miss the heart of the issue.

“I've done probably about nine or ten interviews with folks who are interested in this project, right,” he said. “No one has asked me, which is the critical thing: Why is this such a big deal?”

While a number of books have been written about the history of Macon-Bibb, few people before now have acknowledged the extensive role slavery played in the county’s story. Fontenot said there shouldn’t be a need for this research project, topics like this should already be widely understood. The documents should never have been tucked away — they should already be in the public record.

The link to the database is currently available at bibbclerkindexsearch.com/external, and anyone may access the documents.

The next stage of the project is to create a larger digital platform that will feature the database as well as other research projects throughout Middle Georgia in the field of Africana studies. The project will be titled “Digitizing Black Life and Culture in Middle Georgia.”

Fontenot hopes that more courthouses and scholars working in the field will become interested in the project and realize they need to do it as well.

“A far-reaching effect of this is, as far as I'm concerned, is to be able to generate enough interest in the value of doing this kind of work and making these kinds of documents available to people," Fontenot said.

At BEAR Day, Mercer’s annual research presentation day, two of Fontenot’s students presented their work on the project and invited him to come. When he stepped into the lecture room, he was surprised to find that it was standing room only. The energy in the room was infectious.

He realized so many people cared about the project; it mattered to them.

This is what his professors meant when they said that as a student, the best thing he could do was work within the system and change it from the inside out.

“I was talking about this with my students in class one day,” Fontenot said. “They asked, ‘Well, what happened to your revolution?’ I said, 'You're part of it.' I'm turning out revolutionaries. So this project is part of my revolution.”

Eliza Moore ‘24 is an English and Journalism student at Mercer University. She is now in her second year working as The Cluster’s News Editor after a semester abroad. She is currently producing work for Macon Magazine and Georgia Public Broadcasting in addition to her work with The Cluster. She loves breakfasts, the ocean, and all things related to writing.