There is comfort in knowing that you are not defined wholly by your past, and that no matter what you have done before this moment, you are not restricted by those actions. While not unaffected by your actions, you are free to move forward and become the best version of yourself.

However, this freedom has a cost; one’s past innocence does not excuse their present actions. No matter your perceived virtue or supposed success, if you sexually assault an unconscious woman and run when confronted, you may not cry, “I am not a rapist; I just messed up,” for indeed you are, and forever shall be, one who has raped another.

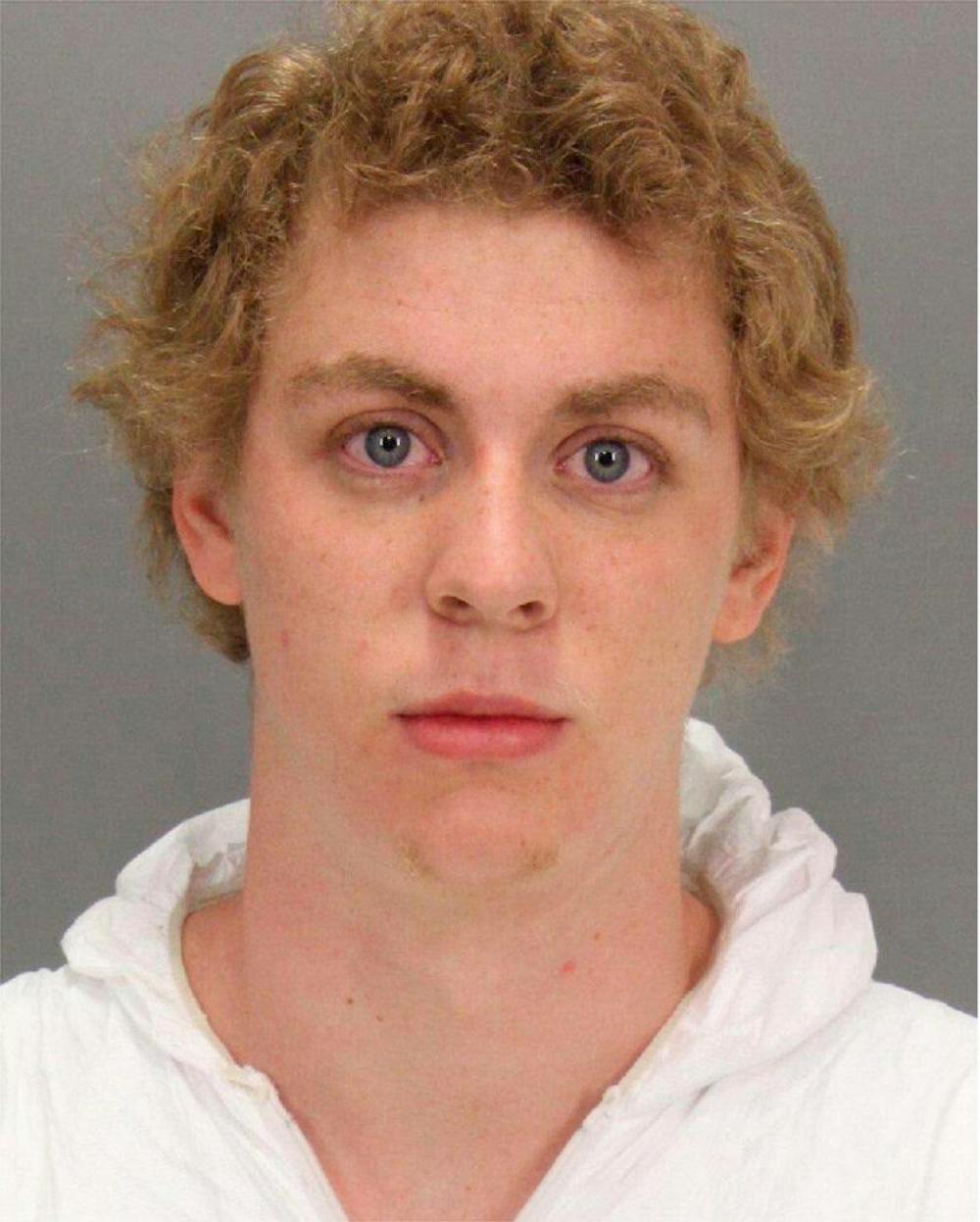

Brock Turner, or as the media has affectionately coined him the “Stanford Rapist”, was released Sept. 2 after three short months in prison.

For the small number of readers who are not self-proclaimed experts on this case and all things ethical, Brock Turner, a three time All-American swimmer attending Stanford University, was convicted of three counts of felony sexual assault for the rape of a 22 year old woman, whose name is not public knowledge. His crimes warranted a sentence of up to 14 years in prison. He was sentenced for a mere six months, and he only served three.

A constant stream of vitriol and boiling hatred came spewing up from the bowels of the Internet for about a solid week and a half after this, which was impressive considering the child-like attention span of the American public. But now, we have the unique opportunity of considering the crimes of Brock Turner in hindsight.

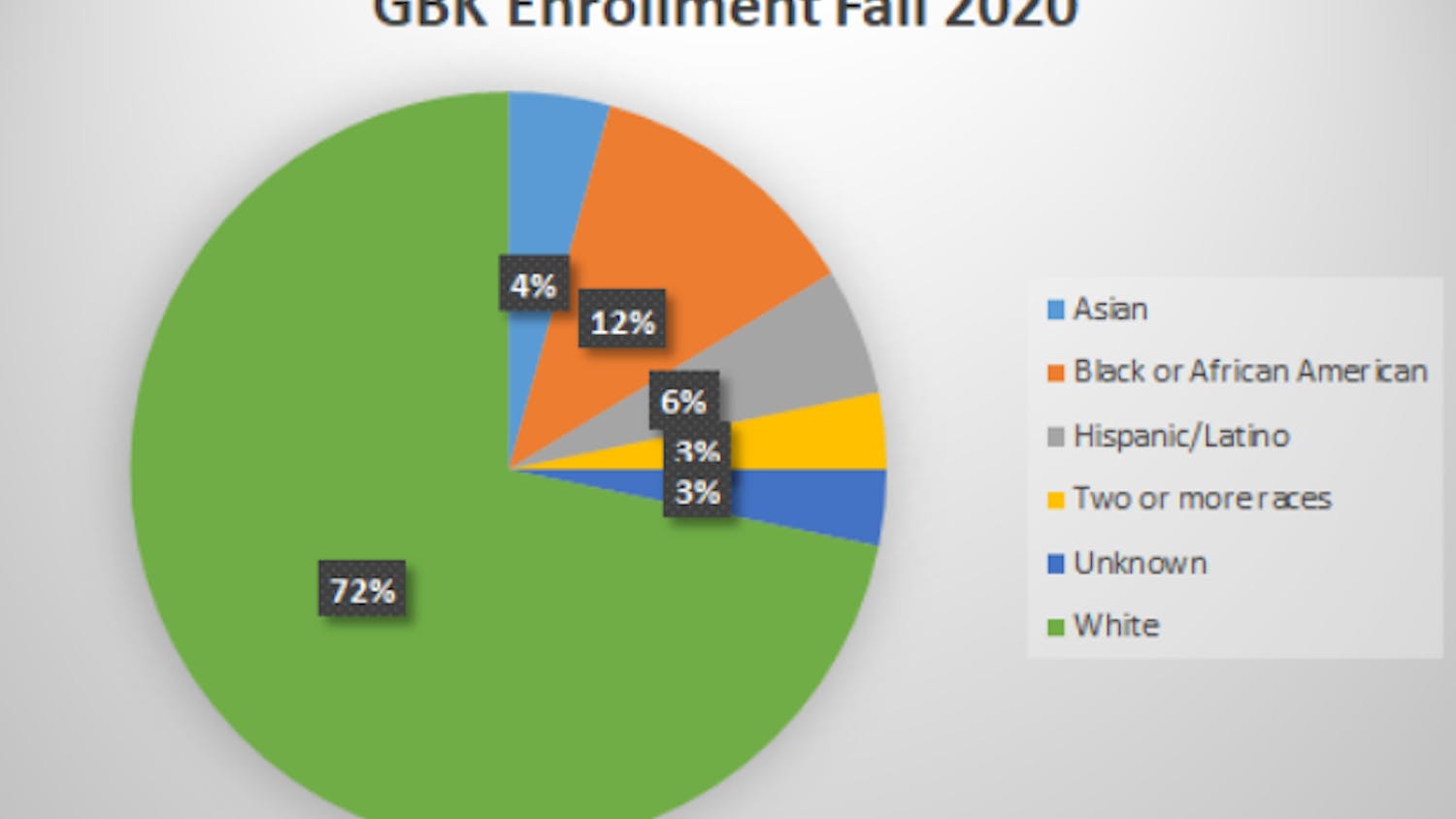

“White, male privilege” is the phrase most commonly associated with this sleight of justice, yet the real, core issue is even deeper than ingrained, cultural bias. Privilege is another symptom of an even darker problem. It is a breed of weakness that demands our attention here.

Brock Turner was not a saint one day and a rapist the next. His life, one of ease and popularity, is one in which his appetites have never been checked at the door, for his hand has never been refused what it desires. The strength of Turner’s spirit was not one tried by fire, if you will. His soul has been fenced in from the hard decisions of life and was therefore not suited to withstand the obstacle of his temptation. This is not to say he is not responsible, but serves as an explanation of his actions.

Some call this privilege, but that is to let him off too easy. To say that it is privilege is to make it innate, unavoidable. If Brock was let off because he was white, then he is not at fault, for he has no control over his skin color. If his guilt is associated solely with his ethnicity, then we withhold from him the grim that his deeds are due. Those who do not find virtue by experience must have another standard, or the law will substitute this plumb line for them.

However, the law also failed the victim, for the judge who was supposed to represent the strong arm of the legal system was also weak. His weakness consists of an inversion of Turner’s. He allows his law to dominate the law he was supposed to represent.

Justice failed the victim of Brock Turner’s passion because the law is not absolute. It depends on the moral fortification of those who execute it.

Opinion: Brock Turner’s prison sentence not simply the result of privilege